Foundation Models: From Point Solutions to “Generalist” Medical AI

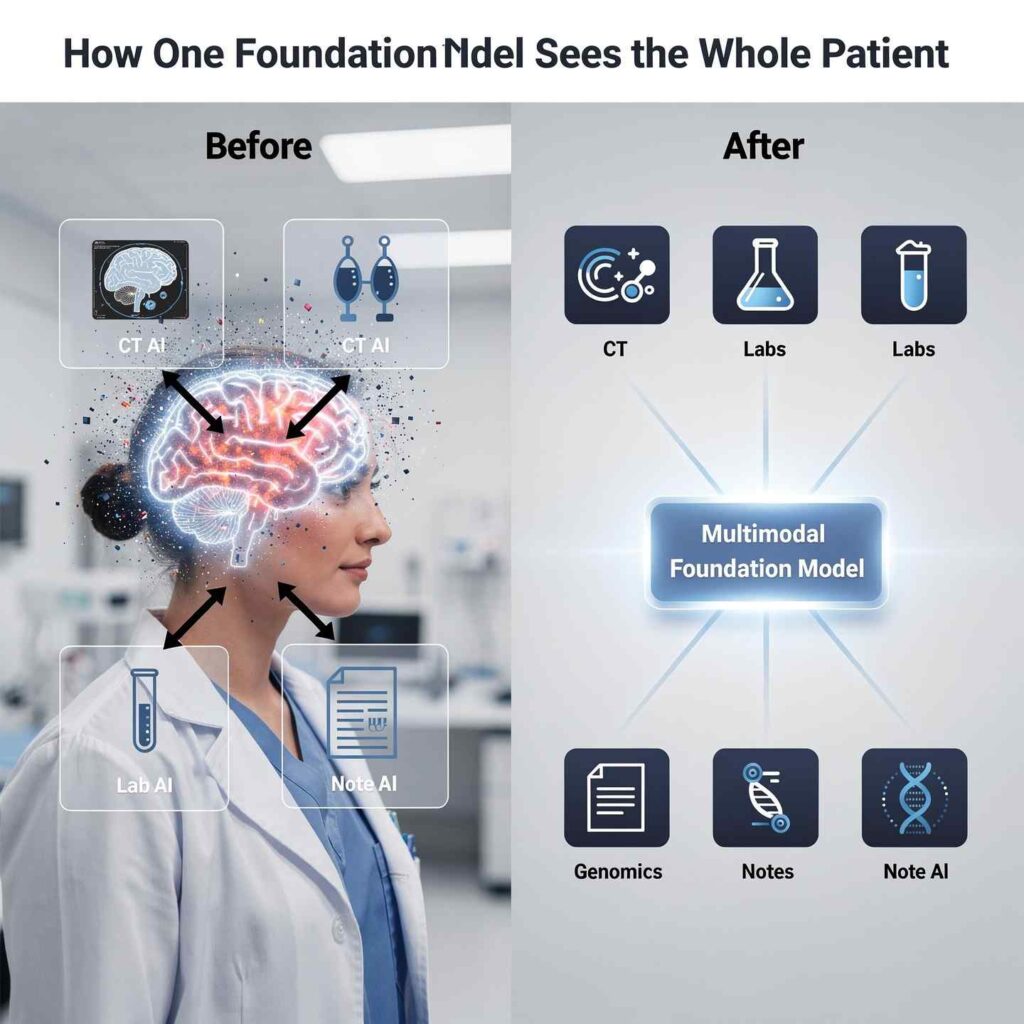

For years, medical AI has largely meant narrow tools: one model to spot lung nodules on CT, another to predict 30‑day readmissions, a third to extract problems from notes. Each system worked in its own silo, trained on its own data type. That made sense technically, but it does not match how clinicians think or how patients present: as whole people, not as isolated images or lab values.

Medical multimodal foundation models (MMFMs) are changing this picture. These large, pre‑trained models are designed from the start to handle many data types at once—clinical text, imaging, structured EHR data, time series, and sometimes genomics. Once trained, the same model can be adapted to diagnose disease, estimate risk, support treatment decisions, and even generate synthetic patient‑like data. In short, they behave much more like “generalist” medical AI systems than the single‑task tools clinicians are used to.

Recent reviews describe MMFMs as a new paradigm that integrates diverse biomedical data “into a unified pretrained architecture for downstream diagnostic, prognostic, and generative tasks.” That shift has big implications for precision medicine, workflow design, and how health systems think about AI strategy.

How Multimodal Foundation Models Actually Work

Under the hood, MMFMs follow a few common design principles.

1. Modality‑specific encoders

Each data stream has its own encoder network:

- Vision encoders (CNNs or vision transformers) for radiology and pathology images

- Text encoders (transformers) for clinical notes and reports

- Sequence encoders (RNNs, transformers) for EHR event streams and time‑series (labs, vitals, waveforms)

- Specialized modules for genomics or wearable sensors

These encoders transform raw inputs into feature representations. Those representations are then projected into a shared latent space so different modalities can “talk” to each other.

2. Cross‑modal fusion with attention

Once everything is in this shared space, the model uses transformer‑style multi‑head attention to perform cross‑modal reasoning. For example:

- An imaging token (a patch of CT scan) can attend to relevant words in a radiology report.

- A lab token (like creatinine) can attend to certain segments of a pathology slide or line in a progress note.

This attention‑based fusion lets the model learn clinically meaningful relationships across modalities—such as linking a pattern on MRI to a specific genetic signature and lab profile.

3. Self‑supervised and contrastive pre‑training

Labeling medical data is expensive. To reduce dependence on annotations, MMFMs rely heavily on self‑supervised and contrastive objectives:

- Masked modality modeling: hide parts of one modality and train the model to reconstruct them, forcing it to infer across modalities (for example, predict missing labs from images and notes).

- Contrastive learning: pull together representations of matched modalities (image–report pairs) and push apart mismatched ones, aligning text and image spaces.

- Proxy tasks: like segmentation, retrieval, and report generation to help the model learn structure before being fine‑tuned on clinical endpoints.

After this large‑scale pre‑training, relatively small “heads” or adapters can be added for specific clinical tasks—like predicting survival, classifying disease, or generating a summary—without retraining the whole system.

What These Models Can Already Do

Recent surveys and position pieces highlight a wide range of capabilities for MMFMs in clinical care.

1. Integrated Diagnosis and Differential Generation

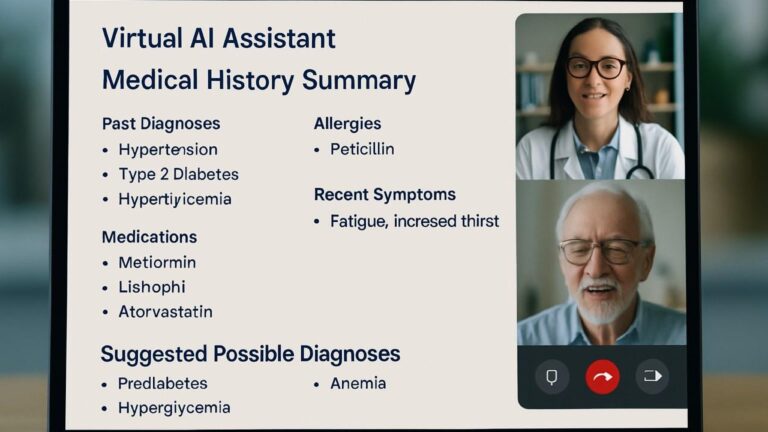

Because MMFMs see multiple data types at once, they can move beyond “find this lesion” toward richer clinical questions:

- Given CT + lab trends + EHR notes, estimate the likelihood of pulmonary embolism vs pneumonia vs heart failure.

- Given MRI + pathology slide + genomics + staging text, suggest a likely tumor subtype and stage and highlight discrepancies.

Benchmarks summarized by Emergent Mind show that in oncology tasks, multimodal models have achieved AUC around 0.92 vs 0.85 for imaging‑only baselines, indicating meaningful gains from cross‑modal fusion. In cardiology and neurology, AUC improvements of 5–8 percentage points and better calibration have been reported when combining imaging with structured and text data.

2. Risk Stratification and Survival Prediction

MMFMs also excel at risk modeling and survival analysis:

- Combining histology images, gene expression data, and pathology text has pushed the concordance index (C‑index) for survival prediction up to about 0.79, outperforming unimodal approaches.

- EHR‑centric multimodal encoders have reached AUROC ≈ 0.88 for ICU mortality prediction on MIMIC‑IV when fusing structured data with imaging and text.

These models effectively learn richer “risk fingerprints” across modalities, which supports more personalized prognosis and follow‑up planning.

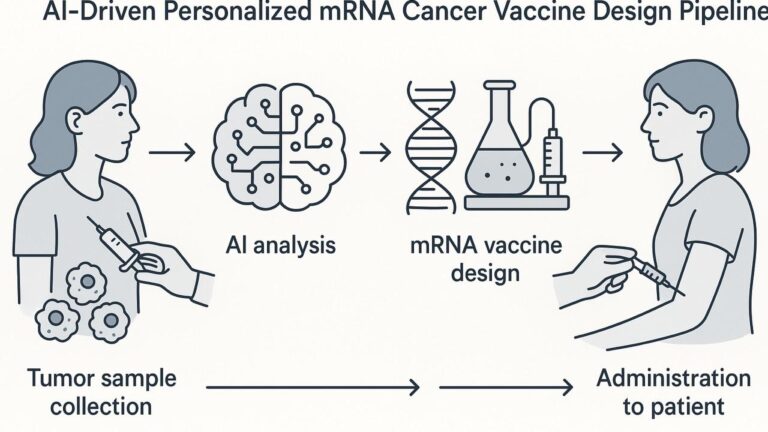

3. Precision Treatment Support

In the review by Sun et al., MMFMs are described as being adapted for tasks “from early diagnosis to personalized treatment strategies,” including predicting treatment response and toxicity using combined imaging, EHR, and omics data. For example:

- In oncology, models can integrate tumor imaging, molecular markers, and past therapy history to estimate which regimen is most likely to succeed.

- In cardiology, they can combine echo videos, ECG traces, and lab series to predict who will benefit from a particular device or drug.

In most cases, these systems are still decision support, not automated decision‑making—but they can surface patterns and risk profiles humans might miss.

4. Synthetic Multimodal Data Generation

One of the more surprising capabilities is joint synthetic data generation. Newer foundation models like XGeM (cited in the Emergent Mind overview) can generate realistic, linked synthetic data across modalities—for example, an image, corresponding text report, and matching lab profile.

Studies show:

- Classifiers trained on synthetic multimodal data can reach performance very close to those trained on real data (AUROC ~0.75 vs 0.74 in one setup), and

- Synthetic data can improve F1 scores by balancing rare classes that are under‑represented in real datasets.

That opens the door to better model training in rare diseases and more privacy‑preserving data sharing.

Why This Is a Big Deal for Healthcare

The shift from single‑task, single‑modality AI to generalist MMFMs has several important implications.

1. Closer to How Clinicians Actually Work

Clinicians rarely make decisions based on a single image or lab value. They integrate:

- Imaging

- Physical exam and history

- Labs and vitals

- Pathology

- Prior responses and comorbidities

MMFMs are built to mimic this integrative reasoning by design. That makes their outputs—like differential lists and risk scores—more aligned with real‑world decision‑making.

2. Fewer Point Solutions, More Unified Platforms

Health systems currently juggle many separate AI tools: sepsis alerts, imaging triage, readmission prediction, each from different vendors. Foundation models promise a different approach:

- One core model, adapted to multiple tasks via light‑weight heads or prompts.

- Lower marginal cost to add new tasks and modalities.

- More consistent behavior and governance across use cases.

A 2025 systematic review notes that multimodal foundation models are explicitly designed for parameter‑efficient adaptation with techniques like LoRA adapters, enabling multi‑task expansion without full retraining.

3. Stronger Performance With Less Labeled Data

Because of their heavy use of self‑supervised and contrastive pre‑training, MMFMs can reach good performance on new tasks with much less labeled data than traditional models. That matters particularly for:

- Rare diseases

- Under‑studied populations

- High‑cost labels (for example, expert‑annotated pathology or complex outcomes)

4. Enabling Truly Personalized, Multimodal Precision Medicine

Precision medicine has always promised to integrate genomics, imaging, labs, and environment. In practice, those streams are often analyzed separately. MMFMs, by design, bring them together in one representational space.

That makes it easier to:

- Identify multi‑omic subtypes of disease

- Match patients to therapies based on full profiles, not one biomarker

- Build better digital twins that simulate individual trajectories

Key Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, MMFMs face serious technical and implementation hurdles.

1. Missing and Imbalanced Modalities

In real life, not every patient has every data type:

- Many have labs + notes but no relevant imaging.

- Others have imaging but no genomics.

Training robust fusion models that still work when one or more modalities are missing is an active research area. Techniques like masked modality modeling, generative completion, and curriculum learning are being explored but are not yet perfect.

2. Domain Shift and Generalization

Models trained at one institution may see:

- Different scanners or acquisition protocols

- Different note styles and coding patterns

- Different patient demographics

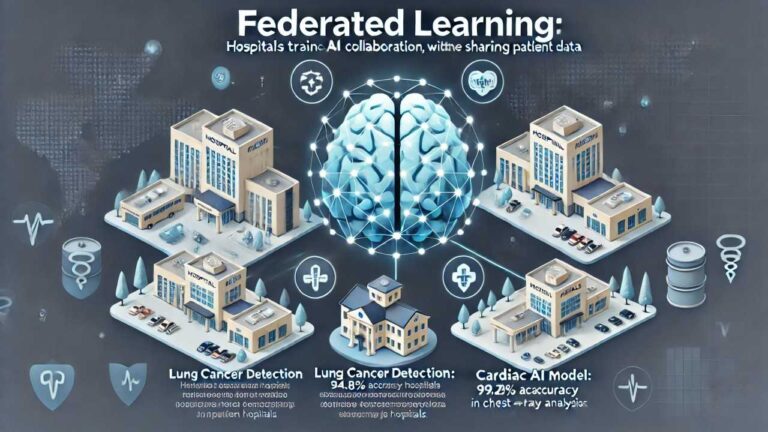

Without careful design and validation, MMFMs can suffer from domain shift. Reviews highlight the need for federated learning and privacy‑preserving aggregation so models can learn from diverse sites without centralizing sensitive data.

3. Interpretability and Clinical Trust

When a model blends many sources, it becomes even more important to understand why it produced a given output. Current approaches include:

- Cross‑modal attention maps (showing which pixels, words, and lab values were most influential)

- Saliency maps on images (for example, Grad‑CAM)

- Concept bottleneck and SHAP‑style explanations on structured features

Even so, many clinicians and regulators still see these systems as black boxes. Guidelines like FUTURE‑AI stress explainability, robustness, and prospective evaluation as prerequisites for deployment.

4. Compute, Infrastructure, and Governance

Training and serving MMFMs requires substantial:

- GPU/TPU resources

- High‑bandwidth access to PACS, EHR, and omics systems

- MLOps frameworks for model versioning, drift monitoring, and audit trails

On top of that, organizations must build governance:

- Clear approval processes

- Clinical champions and oversight committees

- Policies for “AI override” and clinician accountability

Real-World Example Scenarios (Conceptual)

While many MMFMs are still in research, here are realistic scenarios based on current capabilities:

- Oncology Tumor Board Assistant

- Inputs: CT/PET, pathology slides, mutation panel, clinic notes.

- Output: suggested stage, risk category, likely prognosis, and guideline‑concordant treatment options—with linked evidence from each modality.

- ICU Deterioration Predictor

- Inputs: chest X‑ray, ventilator waveforms, labs, nursing notes.

- Output: near‑term risk of ARDS or sepsis, with highlighted factors and trend plots.

- Rare Disease Triage

- Inputs: MRI, genetic testing results, symptom descriptions, family history.

- Output: ranked list of rare syndromes to consider, plus suggested confirmatory tests.

All of these use the same backbone model, fine‑tuned differently, which is the core “generalist” idea.