AI Enables Remote Neuropsychiatric Assessments: Video-Based Analysis of Speech and Facial Cues for Depression and Anxiety

The rapid expansion of telehealth has made psychiatry more accessible, but it has also changed how clinicians gather information. Body language, micro‑expressions, and subtle shifts in speech that are easily noticed in the clinic can be harder to appreciate through a laptop camera. At the same time, millions of people with depression and anxiety never reach a specialist at all. AI‑assisted analysis of video—focusing on speech, facial expressions, and other behavioral cues—offers a way to make remote neuropsychiatric assessment more objective, scalable, and continuous, without replacing the clinician at the center of care.

Growing evidence shows that machine‑learning models can extract mental health “digital biomarkers” from ordinary video calls and recorded interviews, with impressive accuracy in detecting and grading depression and anxiety symptoms. When embedded into telepsychiatry and remote monitoring workflows, these tools could extend expert assessment beyond the clinic and enable earlier intervention.

Why Speech and Facial Cues Matter in Remote Assessment

Psychiatric diagnosis has always relied heavily on observable behavior:

- Speech: rate, volume, prosody, latency, spontaneity, coherence.

- Affect and facial expression: range, intensity, congruence with content, micro‑expressions.

- Motor behavior: psychomotor agitation or slowing, gestures, posture.

Depression and anxiety predictably alter these domains. Depressed patients may speak more slowly, pause longer, use a flatter tone, show reduced facial expressivity, and move less. Anxious patients may have more tense facial muscles, widened eyes, quicker speech, or more fidgeting.

Modern AI systems can quantify these phenomena frame by frame and millisecond by millisecond:

- Computer vision tracks facial landmarks, facial action units (AUs), gaze, and head movement.

- Speech processing algorithms capture pitch, jitter, shimmer, pause structure, articulation rate, and spectral features.

- Language models analyze word choice, sentence structure, and semantic content.

These signals can be extracted from standard telehealth video or smartphone recordings, with no special hardware beyond a camera and microphone.

What the Evidence Shows: Accuracy for Depression and Anxiety

Cross‑Sectional Accuracy from Video and Audio

A 2023 study of 319 older adults with mild cognitive impairment recorded brief video interviews and extracted both speech and facial features. Depression and anxiety were assessed with standard scales (PHQ, GAD). Machine‑learning models trained on these digital features achieved:

- Depression detection accuracy up to 95.8% in men and 87.8% in women.

- Anxiety detection accuracy up to 96.1% in men and 88.2% in women.

Specific facial action units (e.g., AU10, 12, 15, 17, 25, 26, 45) and spectral/temporal speech features were differentially associated with depression and anxiety, suggesting distinct “digital signatures” for each condition.

In another line of work, a deep learning model using facial expressions and body movement from video was able to estimate depression severity in real time, correlating well with standard rating scales. The model introduced a behavioral depression degree (BDD) metric based on expression and movement entropy and showed that multi‑modal video (face + body) outperformed any single modality.

Systematic Reviews and Meta‑Analyses

A 2025 diagnostic accuracy systematic review pooled results from 30 studies using AI to detect depression from behavioral cues—speech, text, movement, and facial expressions.

- Reported accuracies ranged from about 80% to nearly 100%, with a mean around 93%.

- Speech and facial expression tended to show higher sensitivity (better at identifying true cases), while text and movement provided higher specificity (better at ruling out non‑cases).

A separate 2025 systematic review focusing on AI‑based recognition of facial and micro‑expressions for mental and neurological disorders found similar performance:

- Across 36 eligible studies on conditions including depression and anxiety, average diagnostic accuracy was roughly 93%, with F1‑scores often between 0.87 and 0.99.

- Multimodal models (combining face, voice, or other signals) consistently outperformed unimodal ones.

These reviews support the idea that behavioral video and audio signals are rich enough to support clinically useful detection of depression and anxiety, at least in controlled research settings.

Multimodal Conversational Agents

Moving beyond offline analysis, some teams have evaluated live, cloud‑based conversational agents that capture and analyze behavior during remote interviews.

In one study, a multimodal dialog system (“Tina”) conducted semi‑structured interviews with participants experiencing depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideation. During sessions, the platform streamed:

- Speech acoustics.

- Language content.

- Facial movement data.

Machine‑learning models built on these data were then used to classify mental states:

- Facial information was especially informative for anxiety classification.

- Speech and language were more discriminative for depression and suicidality.

- Combining all three modalities improved performance on all classification tasks compared with any single modality.

A broader narrative review of AI in mental health similarly notes that multimodal telepsychiatry systems—integrating facial micro‑expressions, vocal tone, and verbal content in real time—can flag subtle signs of depression and anxiety that might be missed in standard video calls, and generate continuous risk scores during virtual consultations.

How These Systems Work in Practice

Data Capture in Telehealth or Home Settings

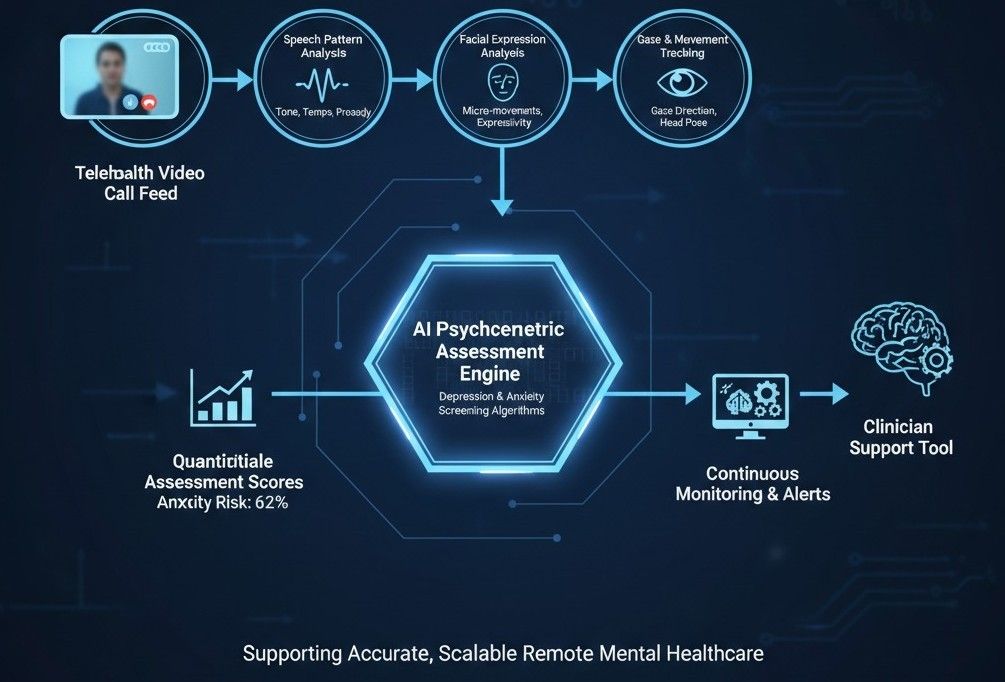

Most remote neuropsychiatric systems follow a similar pipeline:

- Video/audio capture: A standard telehealth platform or app records short clips (for example, 5–15 minutes of conversation, reading tasks, or guided questions).

- Feature extraction:

- Computer vision identifies facial landmarks, gaze direction, and action units frame by frame.

- Audio processing extracts pitch, intensity, speaking rate, pauses, and spectral characteristics.

- NLP models analyze transcribed text.

- Model inference: A trained ML or deep learning model outputs:

- Probability of depression or anxiety above a clinical threshold.

- Estimated severity (e.g., predicted PHQ‑8 or GAD‑7 scores).

- Longitudinal trends across sessions.

- Clinician‑facing summary: Results are embedded into the telehealth interface or EHR as:

- Risk flags (low/medium/high).

- Visualizations of behavioral changes over time.

- Notations that can support—but not replace—clinical judgment.

Some emerging systems aim to run parts of the pipeline on‑device, preserving privacy and enabling low‑latency feedback during live video visits.

How Accurate Is “Remote” Compared with In‑Person Assessment?

Traditional telepsychiatry, even without AI, is already reasonably robust. A 2024 systematic review comparing psychiatric diagnosis via live telehealth (video or phone) versus face‑to‑face interviews found good agreement and reliability across conditions including depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and social anxiety disorder. This suggests that remote formats do not inherently degrade diagnostic quality when structured properly.

AI‑assisted tools aim to augment telehealth further by:

- Providing additional objective behavioral measures.

- Reducing reliance on self‑report alone.

- Helping standardize assessments across different clinicians and settings.

Evidence to date suggests AI models can match or exceed standard questionnaire performance in research environments, but real‑world deployment still requires careful validation and oversight.

Use Cases: From Screening to Ongoing Monitoring

1. Scalable Screening in Primary Care and Community Settings

Given time constraints and stigma, many patients do not complete mental health questionnaires. A short, AI‑analyzed video check‑in (via a kiosk, app, or nurse‑guided tablet) could:

- Provide an objective “second opinion” on depression/anxiety risk.

- Flag patients who should receive a full clinical assessment.

- Aid in routine screening for populations like students, older adults, or patients with chronic medical conditions.

A psychologically interpretable framework (emoLDAnet), for example, used video‑recorded conversations with facial expressions and physiological signals to screen for loneliness, depression, and anxiety, achieving F1‑scores above 0.8 and moderate‑to‑strong correlations with standard scales—supporting its use for large‑scale early screening.

2. Enhancing Telepsychiatry Sessions

In specialist care:

- AI systems can run passively during video visits to generate continuous scores of affective state, psychomotor change, or engagement, which the clinician can review after the session.

- They can help track treatment response over weeks by providing consistent, quantitative measures of expressivity, speech patterns, and interaction style.

For example, longitudinal digital phenotyping work has shown that changes in mobility, sleep, and speech correlate with shifts in stress, anxiety, and mild depression; combining these with video signals could further enrich remote follow‑up.

3. Early Warning and Relapse Detection

Over time, each patient’s digital “baseline” of facial and speech behavior can be established. Deviations from this baseline—such as a progressive reduction in facial expressivity or slowing of speech—may signal:

- Worsening depression.

- Increasing anxiety or restlessness.

- Imminent relapse in recurrent mood disorders.

Early digital phenotyping studies and multimodal depression frameworks show promise for predicting episodes based on behavioral change, though predictive performance is not yet at routine clinical‑decision thresholds.

Limitations, Risks, and Ethical Considerations

Despite exciting results, several constraints and concerns must be acknowledged:

- Generalizability: Many studies are small, single‑site, and use curated datasets; models may underperform in more diverse real‑world populations or on low‑quality consumer video.

- Bias and equity: If training data underrepresent certain ethnicities, ages, or genders, facial and speech models may be less accurate—or systematically biased—for those groups. Systematic reviews emphasize the need for diverse datasets and fairness auditing.

- Privacy and consent: Video and audio of psychiatric interviews are highly sensitive. Robust encryption, on‑device processing where possible, and clear consent for secondary AI analysis are essential.

- Overreliance and false positives/negatives: AI outputs should never be considered standalone diagnoses. Misclassifications could cause undue anxiety or missed cases. Frameworks like FAITA‑Mental Health stress rigorous evaluation of credibility, crisis management, and user agency before clinical use.

- Explainability: Black‑box scores are less useful than models that map back to interpretable behavioral markers (for example, “reduced facial expressivity and slower speech compared with last visit”), which reinforce rather than undermine clinical reasoning.

Regulators and professional bodies are starting to outline assessment frameworks, but there is not yet a universal standard for validating AI‑based neuropsychiatric assessment tools.

How This Fits into the Future of Mental Healthcare

Taken together, the evidence points toward a hybrid model:

- Clinicians remain responsible for diagnosis and treatment, but are supported by AI‑derived behavioral insights during remote and in‑person care.

- Short, structured video assessments—either clinician‑led or automated—become routine components of screening, intake, and follow‑up.

- Digital phenotyping from smartphones and wearables is fused with video‑based cues, providing a richer, more continuous picture of mental health.

- Training programs begin to include modules on interpreting AI‑derived behavioral metrics and understanding their limitations.

If developed and governed well, AI‑enabled remote neuropsychiatric assessment could make high‑quality mental health evaluation more accessible, more objective, and more preventive—reaching people who would otherwise go undiagnosed until their conditions become severe.